Latest Contributions

Memories of Chandni Chowk and India’s First Independence Day

Category:

Vijay studied in Delhi at Jain Primary School Chandni Chowk, Ramjas School No. 1, Hindu College, and Delhi School of Economics (M.A.). He went on to study at the University of Alberta, University of Sheffield, and got his Ph.D. from Michigan State University. At the Delhi School of Economics, he was part of the first batch of students taught by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. At Delhi’s Institute of Economic Growth, he was a research assistant to P.N. Dhar and also assisted V.K.R.V. Rao in his research. He is the author of several technical books on Statistics. He was a professor at Catholic University and Bowling Green State University (BGSU), and is now Professor Emeritus at BGSU. He lives in Potomac Falls, VA. His e-mail is vrohatg@bgsu.edu

Chandni Chowk

My family has lived on Dharampura gali (street) in Chandni Chowk - the heart of old Delhi -for many decades.

Our house is about half a mile from the Red Fort (Lal Kila) and less than half a mile from the Jama Masjid. You can see both monuments from the roof of my Delhi home.

Despite this proximity to the Fort, in the 1940s our only connection to white people (whom we referred to as Vilayati or Angrez, meaning British) was through the frequent Vilayati visitors to the Digambar Jain Temple across our house. These tourists were either from New Delhi's diplomatic community, or they were British soldiers (in civilian clothes) from the Fort.

The Vilayatis visiting the Jain temple usually had a camera around their neck with a leather strap. They were required to take off all leather goods on their bodies before being allowed to enter the temple. Before he died in 1707, Aurangzeb, the Mughal Emperor, had allocated the land in the Chandni Chowk area to the Jains of Delhi. However, the temple, however, was built in 1800-1807, when Raja Harsukh Rai, the imperial treasurer to Shah Akbar (also known as Mirza Akbar or Akbar II) obtained imperial permission to build a temple in the Jain neighbourhood of Dharamapura, just south of Chandni Chowk. The temple, also known as Naya Mandir, is well known for its fine carvings.

In pre-independence India, Chandni Chowk was a broad, well-lit major shopping area. There were few, if any, hawkers on the sidewalk, and so there was plenty of open space. The street begins at Thandi Sarak (now Netaji Subhash Marg). On the south side, there was (and still is) the well-known Bird Hospital, run by the Jain community. The hospital was opened in 1929. It mainly treats pigeons, and also doves, parrots, sparrows, and occasionally peacocks, but it does not treat birds of prey. It frees all birds after their recovery. At any given time, there are three to five thousand birds in the hospital.

The Jain Lal Mandir sits adjacent to the Bird Hospital. Built in 1656, it is the oldest and the best- known Digambar Jain temple in Delhi. Next door is the Gauri Shankar Mahadev Mandir, a Shiv Temple built in 1761 by a Maratha Brahmin. In the 1940s there were (and still are) colourful stalls of flower vendors outside the temple. Many street photographers plied their trade next to flower stalls. That is where one went for black and white passport or any other officially required photographs.

On our gali and surrounding galis there were many shops owned by Muslims. They were small merchants, whom we always called Miyan ji, or Miyan Sahib (terms of respect). They were usually bearded, sold kites, knickknacks, candy, and small toys. We had high regard for these Miyan Sahibs who were very friendly and always extended credit to us kids. While no Muslim families lived on our street, nearby there was Ahmad ka Mohalla a U-shaped street, now called Krishana gali. It was inhabited solely by Muslims, and gossip had it that they were all rich.

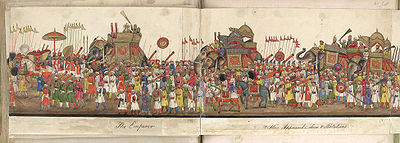

A road from Chandni Chowk runs down to Red Fort's Lahori gate. I remember seeing parades that started from the Fort and came into Chandni Chowk. These parades were started by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. The British revived the tradition after the Darbar in 1903, but on a smaller scale. The parade usually consisted of a marching band of thirty or forty members, in their ceremonial kilts, who played flutes and drums. For me, it was a spectacular sight. The parade ended near Gurudwara Shish Ganj. The Gurudwara was built at the site where Aurangzeb beheaded Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh guru, in 1675. Permission to build the Gurudwara was granted in 1783, but construction began only after the 1857 revolt against the British.

Changes in Chandni Chowk after Partition

The partition of India brought many changes to Chandni Chowk. Sometime around 15 August 1947 all the Muslim owned shops were looted. I was too young to understand why. My father would not allow his children to be a part of the looters, and we never took anything home from these shops. Ahmad ka Mohalla was similarly looted. I remember seeing a large number of people walking away with large silver spittoons, utensils, bed head-boards and other silver articles from this street.

We wondered what happened to the people living in this street. There was no attempt by the neighbourhood leaders or by the police to stop the looting. The residents were evacuated either by the Government or by their Muslim protectors in the middle of the night. Perhaps they went to Jama Masjid. We never knew where they went, but it was a source of intensive speculation in our community. All this happened well before we heard of communal riots.

Those were frightening days for people living close to Jama Masjid. There were constant rumours of impending attacks by the Muslims who had supposedly assembled in Jama Masjid. Men living on our street assembled on their rooftops with water buckets just in case some bomb was thrown from the Masjid. We did not sleep for many nights. But there was no attack. Indeed, there were no hordes of Muslims in the Masjid, as we later found out. That was the only time I remember that the heavy gates to the street were closed and guarded by chowkidars.

In any event, we did not hear much about the mass killings and riots at that time. There was little or nothing in the newspapers or on the radio. We only came to know of problems between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs when suddenly all the houses in Ahmad ka Mohalla were taken over by people who looked different from Delhi wallahs. We were told that they were refugees from Pakistan. Thereafter we began to see refugees everywhere in Dharampura gali and Chandni Chowk area.

The influx of refugees changed the local scene in old Delhi. Streets became crowded. Many schools started running two shifts with several sections of each class. New words were added to our vocabulary and newer foods were introduced to our diet. Thus, kulche-chole and bhatures, unknown to us earlier, became common street foods. Even the shape of our beloved jalebis changed from thin golden crisps to large yellow pieces. The aroma of desi ghee in our streets was overpowered by smells of garlic, onion and vinegar. Even the language changed incorporating phrases such as kee haal hai (how are you), tusi dasa (you tell me),and changa (good).

To accommodate the refugee businesses, a new market, Lajpat Rai Market, was built across from the Fort. It became very popular with the locals. Even the conservative Dariba Kalan jewellery shops began to show changes: machine made and cheaper jewellery began to be sold. The shops became bigger and brighter. Gaddis were replaced by raised platforms, showcases and chairs. Street vendors took over both sides of Chandni Chowk. It soon became so crowded that the tram cars that plied Chandni Chowk had to be discontinued. The locals took all these changes in their stride and pretty soon, the process of assimilation was complete without any strife.

Early schooling

I was a student at the Jain Primary School, which was right in front of our home. It was a complex of buildings consisting of a Dharamsala, a public library, a boy's primary school, a girl's middle school, and the famous Digambar Jain temple.

I remember the school well. It was on the second and third floors of a building that housed the Jain library on the first floor. It had five or six rooms, all used as classrooms, with space for 25 to 30 students each. There were no desks or chairs. As student, we set on dari-pattis (carpet strips) on the floor and used wooden pattis (strips of wood) for a desk. We used slates for arithmetic, and white washable pattis for writing. There was no playground, playroom, or garden. Yet, this was much better than my high school, Ramjas No. 1. There, in the fifth grade, we set under a tin roof in a room that had no windows. Moreover, in the sixth grade, we used a tent as a classroom.

At the Jain School, we were showered with gifts from Jain parents on their sons' admission to the school or on their birthdays. And the gifts were elaborate - all items you needed for the school and a packet of sweets (usually bundi laddoos, imarti, and pedas.) This happened at least two or three times a year. It did not matter which grade the child was in: all the students received the gift. The teachers were friendly and the school was free. Religion was never a consideration in admission and never discussed in the classroom.

Independence Day

In the Jain primary school, preparations for India's first Independence Day celebrations were led by a teacher whose name I do not recall. He was a tall, well-built man in his late twenties always dressed in Khadi pajama and kurta, a Nehru vest and a Nehru topi. He was a drillmaster whom we called Masterji. Masterji told us about the leaders of India, the coming Independence, what it meant to us, and about the celebration that was to take place at the Red Fort on 15 August 1947. Being in the second or third grade, we understood little, but were nevertheless filled with a sense of patriotic pride.

Masterji is the only one I remember from the Jain school. Interestingly, he taught English on the side to anyone who would pay four annas (quarter rupee, 25 paise) a month. Looking back, I wonder how my parents sent me to his English class for it must have been tough for them to come up with the fee. I also wonder why this model citizen of the new India thought of teaching us English at a time when there was so much talk of a National language. I did learn a lot in that class, much more English than I learned in later years.

Several days before 15 August 1947, the galis were cleaned to a shine. Loudspeakers were attached to electricity poles or to chajjas (balconies). The streets were festooned with colourful jhandis (flags), and small Indian flags. One had a feeling that something festive was about to happen!

On Independence Day, Masterji led an early morning flag raising ceremony in the chowk (square) in front of our house and the Jain School. All his class attended and so did many people from the street. After the flag raising ceremony, we sang patriotic songs: Vande Mataram and Jan Man Gan. Sweets were distributed to children. Then we walked to the Parade Grounds to listen to Prime Minister Nehru. The whole ceremony and speeches were broadcast live via All India Radio through loud speakers on our street.

Editor's note: Prime Minister Nehru unfurled the Indian flag and spoke from the Red Fort on 16 August 1947, not 15 August 1947.

The atmosphere at the Red Fort was very festive. Apart from loud speakers and flags attached to every pole, Thandi Sarak was fenced on both sides. There were people all over. The Red Fort grounds were fenced with chairs for dignitaries. We were allowed to be only in the Parade Grounds or in the area near Chandni Chowk. Indian Police, whom you never saw on your street, were everywhere to control the crowd. The crowd was uncharacteristically well behaved with little or no shoving. I had never seen so many people until then in my life. After the speech, also there was much less shoving and pushing so characteristic of Indian crowds. People were in a festive mood and the khomche wallahs (street food vendors) did a roaring business.

People loved to hear Nehru in his characteristic and charismatic style, slow and clear. Later, attending the National Independence Day ceremony at Red Fort and listening to Nehru's speech became a yearly ritual. But in a few years, the excitement of the "Day" was gone. The street flag ceremony continued, but complaints about food shortages, rising prices and scarcity of daily necessities such as rice, atta (wheat flour), soap, and cooking oil, were heard more than statements of national pride!

_______________________________________

© Vijay Rohatgi 2011

Photos from the Internet

Comments

Add new comment