Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

The gap months between high school and college

Category:

Tags:

Amit Shah is a retired publishing executive and owner of Green Comma, a service company for education and social-impact nonprofits. He divides his time between Somerville, MA, and Lovell, Maine, with his wife, Pam, and two cats. His adult sons live in Brooklyn, NY, and Baltimore, MD, respectively.

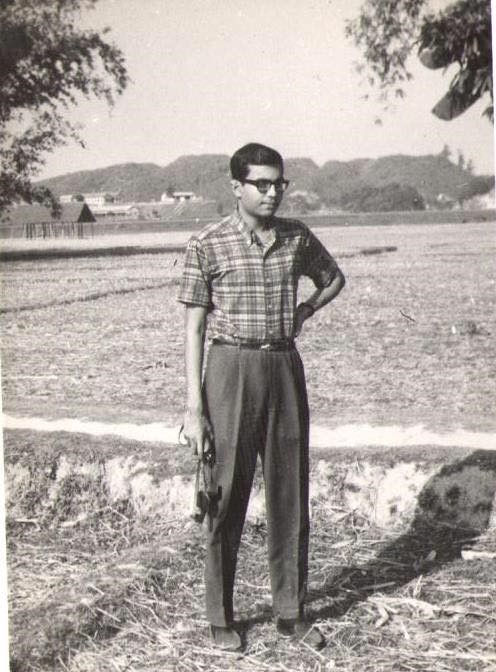

Amit Shah. In the interregnum between high school and college. Jan-Feb. 1967. Silchar, Assam.

In December 1966, when I was sixteen years old, I took the then final exams for high school graduation in Calcutta (now Kolkata). They were the contemporary equivalent of the 12th grade examinations. Called Senior Cambridge O Levels, they were usually tests in seven to eight subject areas. There were three streams of students in those days-humanities, science, vocational/general. I was in the humanities group.

We had to wait for three months for the test booklets to be shipped to the UK and then graded. The results posted were in our respective school notice boards in mid- to late-March. After that, there was a scramble to apply for college admissions, with colleges beginning the academic year in mid-July.

My friend (now deceased) Santanu Sen and I were best buddies all through our school years in Kolkata at LaMartiniere Boys School. His maternal grandmother, Shrimati Jyotsna Chanda, was a member of parliament (Congress) from Cachar district in Assam bordering Bangladesh and present-day Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Mizoram, Nagaland.

Cachar's capital was Silchar, where the family had their house and from where the 1967 election campaign was in progress. I had never been close to a political campaign, and Santanu convinced me that we'd have a great time riding around the countryside following his grandmother and her entourage.

Jyotsna Chanda was the matriarch of the political area in her district. Her father and husband had both been in state-level politics. As a widow with legislative experience, family history, and the resources of a strong central party, she easily beat out her four rivals (all Independents) and got almost 90,000 votes out of a total electorate of about 4.6 million. I don't even remember hearing any opposition bullhorns as we traveled the district.

That's what got me to this field in the photo. We were in the Silchar area for about two weeks. Maybe three.

The 1967 general elections in India were a watershed for the ruling Congress Party. Out of the 16 states only eight returned Congress majorities. Out of 529 Lok Sabha (lower house) seats, Congress secured only 278. The Congress Party leadership also took a beating with political bosses like S.K. Patil and Atulya Ghosh losing their seats.

In March, the exam results were finally posted. Now, I was faced with a choice of either going to one of Calcutta University's colleges (Presidency, Jadavpur, St. Xavier's) or to somewhere outside of Calcutta, namely St. Stephen's College in Delhi or to St. Joseph's in Darjeeling.

Ordinarily, going to Calcutta University for a student who'd grown up in that city was a no-brainer. However, 1966-1967 was not just any other year in Indian history and especially in the east of India.

1966-1967 had the following momentous events that created frustrations and uncertainties, particularly in eastern India:

- food production at historic lows

- the Bihar-north Bengal famine due to severe droughts in the past two years

- communal riots and the constant hartals and strikes

- in May 1967, the first sharecropper uprising in Naxalbari

- the devaluation of the rupee by 56%

The cumulative effect on college campuses in Calcutta was of frustration, anxiety, and rising political militancy that threatened academic institutions and our ability to sit for exams to graduate. This forced us to leave Calcutta. I opted for St. Stephen's in Delhi.

In the summer of 1967, in Calcutta, there were only a handful of teenagers who applied to St. Stephen's, all without much knowledge of the school! We were all good students in high school. We were accepted into "residence", rooms on the college campus. Our subjects were Economics, Physics, Chemistry, Math, History (mine) and English. This scenario is unthinkable in today's Pamplona bull-rush for admission to St. Stephen's, with current cutoff grades that would've thrown all of us out of the running. (As a matter of some pride, I have to report that we did pretty well in university-wide rankings of those years, some becoming the enviable "topper" or first-class first).

I chose History primarily because of my high school history teachers Mr. Menezies and Mr. Peterson, who, though I didn't know it, taught us to question all narratives and facts and to research and develop our own point of view with facts to back them up.

At that time, I thought teaching at the university or becoming a journalist were the two careers that interested me. When I got to college, we were asked to read E.H. Carr's What Is History?, which asks every reader of history to look at perspectives and biases and contextual forces. This predated postmodernists who treat all history as fiction and each historical narrative unraveled as a mystery. Carr's famous conclusion is still what I believe in: "When we attempt to answer the question ‘What is history?' our answer, consciously or unconsciously, reflects our own position in time."

Back to the photo. There I am - in-between leaving my parents and childhood behind, and heading out toward an adult life. Looking back now after 51 years, being so clean-cut and seemingly unruffled, without a clue to what life ahead held in store.

____________________________________________________

© Amit Shah 2018

Editor's note: I approve all comments written by people\; the comments must be related to the story. The purpose of the approval process is to prevent unwanted comments, inserted by software robots, which have nothing to do with the story.

Add new comment